The business of financial advice is set for disruption. Technology continuously offers new ways to engage clients, but it’s also presenting the means to replace many traditional financial professional roles. Baby boomers, Gen X, and the Millennials are more educated, more tech-savvy, and more demanding than any previous generation. Perhaps most importantly, extended longevity, combined with the expectation to live longer and better, is driving clients to demand more from financial advice. Clients now want financial advice to identify and navigate what they may confront in middle age and as older adults. This paper discusses the evolving context of old age and describes a client focused framework to understand what may be considered financial professional value by clients across the generations. Three financial professional value propositions are presented: transaction-based, planning-based, and longevity-based.

Cashing in the Longevity Dividend

In the United States in 1900, life expectancy was 47, which meant midlife crises came early. Today, life expectancy is nearly 80 in the US,1 and those 75 and older are projected to be the fastest-growing group of employees in the labor force.2 Not only are lifespans lengthening, but the number of years someone will be healthy in that time will be longer as well.

Medical advances and technology may extend those years of health even further, granting us a longevity dividend of nearly 30 to 40 years longer than we enjoyed a little more than a century ago. For a couple who are 65 today, there’s a 50% chance that one of them will be alive at age 92.3

Researchers are now suggesting that more than half of babies born today in the industrialized world will live to 100 years, and some are predicting even longer lifespans than that.4 It is now reasonable to begin looking at 100 years of life as the new normal, especially for those with access to good food, water, shelter, education, and—of course—healthcare.

Just imagine living 100 years. Adding decades to the tail end of life changes most things we take for granted about the beginning and middle, such as when childhood and adolescence end and adulthood begins, when and how many times we might go to school, how many careers (let alone jobs) we may have, when we will marry (and for how long), and when we will retire. And importantly, we’ll need to consider the twin questions of how long retirement will span and what it will entail. What will be the specific needs and wants for a relatively undefined period of life that’s increasing in length from just a few years to several decades?

About 10,000 Baby Boomers turn 65 each day.5 Even Gen X is at midlife, with its oldest members in their upper 50s. And while the Millennials (a.k.a. Gen Y) are young and numerous, and the even-younger Generation Z are entering the workforce. While many may discuss the differences between each of these cohorts, an overarching commonality is becoming apparent. They all expect to live longer and better.

Longer life is a dividend to be cashed. Advances in technology, medicine, and everyday life have persuaded all generations that there is, or will be, a product or service to address needs that arise throughout the lifespan. Each successive generation has great expectations that life will continue to get longer and better as they age.

Longevity? There had better be an app for that.

Understanding the New Context of Old Age

If extended longevity and growing numbers of older people were the only demographic realities confronting financial services, the response would be relatively straightforward: more financial products and services to meet the needs of a growing market. However, while the population may be grayer than at any other time in history, the older client today and tomorrow is far different from previous generations. On average, the ‘new’ older client is more educated, tech-savvy, and destined to navigate a very different context of aging than his or her parents.

Educated and Smart: The baby boomers have more education than any previous generation. Educational attainment is on an upward trajectory overall.6 Education, combined with ubiquitous access to information contributes to the attitude that with enough study and research, the optimal decision is always within reach. Retailers from Apple to Whole Foods provide in-store and online environments designed to empower their shoppers to choose the right product. Apple offers its Genius Bar as a place to learn, not just get a broken phone fixed. Whole Foods provides information about the origins, environmental considerations, and quality of its products, along with how to prepare them. Even in fields that require complex decisions such as healthcare, savvy, assertive, health-conscious baby boomers are more likely to research health information.7 Clients now want to not simply access expertise, but to become smarter about their choices, behaviors, and outcomes in nearly every facet of life.

Technology Savvy: High tech is most often associated with younger consumers. However, age predicts technology use and adoption far less than education and income. The baby boomers and each successive generation have become virtually shockproof to new releases of smart phones, notebooks, or ever-wider and more affordable flat-screen televisions. According to the Pew Research Center, nearly 45% of Americans over age 65 years old use at least one social-media site regularly.8 Every generation now expects technology to be part of their daily experience. Most financial professionals’ clients may, therefore, not ask whether there’s an app or website to help them, but rather when the next online improvement will occur, making their experience easier, more personalized, and ubiquitous.

Changing Family Dynamics: The family has traditionally provided the physical and social support necessary to age well. However, the family has changed, leaving an uncertain future for many older people. Fertility has dropped precipitously nationwide.

Where the parents of the baby boomers had 3.9 children on average, baby boomers had only 1.9 children—and births have continued to decline. The total fertility rate—an estimate of the number of babies a woman will have over her lifetime—has generally remained below the “replacement” level of 2.1 since 1971, reaching a record-low in 2019.9

Consequently, there are simply fewer children to provide care and support to aging parents. Even those who do have kids cannot be sure that their adult children will find economic opportunity near home. Many parents in middle age urge their children to seek opportunity in distant cities and states, only to find themselves without family nearby as they grow older. While the new older clients may perceive themselves as resourceful and tech-savvy, their propensity to live longer and better is tempered by both a changing social reality and the rise of new demographic challenges.

The Jobs of Longevity

The eminent marketing theorist Theodore Levitt argued that consumers do not buy products or services per se, but rather hire those products and services to do a specific ‘job.’ Levitt’s often-cited example is the drill. Do consumers really go out to buy a drill because they want to own one, or because they want to drill a hole in the wall? Owning a drill (or any product or service) isn’t the objective—it’s simply a means to accomplish a job. The closer a product or service can get to satisfying a customer’s job, the more valued it is. The most value is derived when consumers perceive what is offered as a comprehensive solution to their needs. Longevity and the context of living longer present new jobs that must be planned for, financed, and ultimately accomplished. Consider just a few challenges for living longer better:

Making Transitions: The effect of longevity on the phenomenon currently known as retirement is evolving. Given that lifespans are rapidly increasing and the traditional concept of old age seems more distant, the need for income, social connections, and a reason to get up in the morning has persuaded many to extend their work life by continuing at the same job as always, switching to a new company, shifting to part-time, or even changing careers. Transitioning from one’s old career to another full-time position or another profession altogether requires planning. While financial implications must be considered, so too must education, technological training, and other unique requirements that may be necessary to make a change, say, from engineer to high-school math instructor.

Managing Health and Wellbeing: Financing healthcare is often discussed as a key factor in financial planning. Average costs typically guide preparation, but hardly anyone is average, or even close to it. Age brings a higher risk of chronic diseases, such as heart disease, cancer, and diabetes—the nation’s leading drivers of healthcare costs. According to the Centers for Disease Control, six in 10 adults in the U.S. manage one chronic disease, while four in 10 have two or more.10 Any one, two, or three-plus conditions will multiply the cost of healthcare in older age. Poorly managed conditions could also jeopardize plans to work longer—the most commonly cited strategy to extend retirement savings. Moreover, the cost of ensuring quality of life while managing multiple conditions is far greater than that of the basic healthcare necessities that are reimbursed by insurers.

Providing Care: For more and more people, informal caregiving is crucial to promoting quality of life in old age. Nearly 42 million Americans were providing unpaid care to an adult age 50 or older in 2020. Informal caregiving can be as simple as a phone call or an occasional ride to the store, or as painstaking as ensuring that medications are taken correctly and bills are paid. An older adult’s typical caregiver is female; an adult child, spouse, or partner.11 That caregiver juggles the challenges of managing her own life and those of loved ones, a complex mix that includes life, work, children, marriage, and eldercare.

Living at Home: Where to live in older age is rarely discussed or planned. While some consider beaches and fairways, relatively few ever make the move to sunnier climates. Even those who wish to downsize must think beyond the vacation vision of retirement to consider what kind of home they can afford, as well as where best to live as their needs change with age.

Currently, most adults age 55 and older intend to stay in their current home for as long as possible, which is often the house that represents their marriage, mortgage, and memories.12 However, staying home presents challenges of its own. Faced with increasing frailty, distant or no children, or even living alone, how does one maintain one’s home?

Performing even such a mundane activity as changing a light bulb can be a hassle—or worse, a hazard. If driving is not a comfortable or safe option, how can older adults ensure seamless transportation to where they need to go, let alone where they want to go?

As difficult as it may be for couples to maintain a home in advanced age, it is even more problematic for those who age alone. Lifestyle choices, an unprecedented high divorce rate among the 50-plus, and widowhood have resulted in 27% of Americans age 60 and older living in solo households— especially women.13

Mapping A New Frontier of Financial Services Advisory

Financial services and advice has traditionally been product-based—focused on a successful investment strategy to provide the resources necessary for retirement. That approach is certainly not incorrect, but extended longevity and the new context of aging have made this value proposition incomplete to clients. Given the new demands and changing context of living longer and better, clients may increasingly search for solutions to the many jobs of longevity. Planning and solving for these jobs, often referred to as longevity navigation or management, presents a new landscape for what clients need, want, and ultimately may pay an advisory firm to provide.

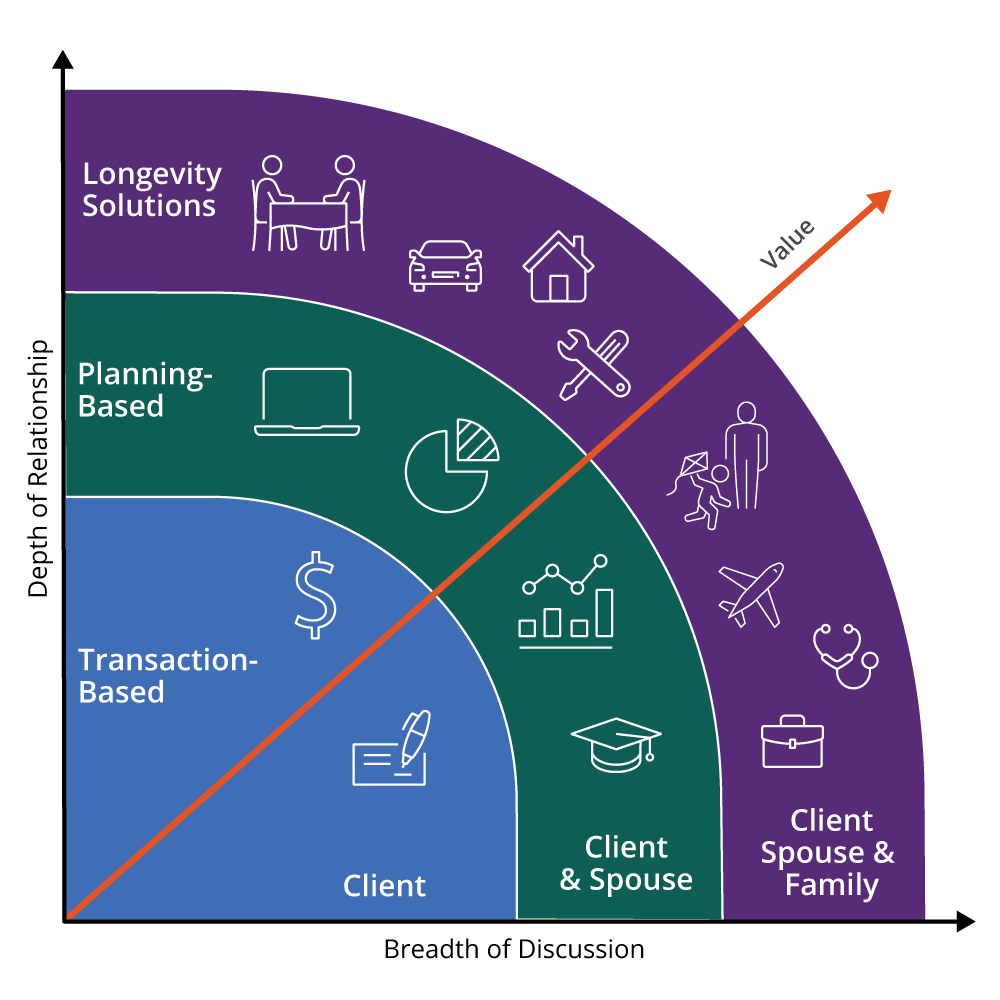

Three financial professional value propositions emerge. (See Figure 1) These may overlap depending on the style of the advisory firm, but for the sake of simplicity, the three propositions, categorized according to financial-planning focus and client relationship, are: transaction-based financial professional, planning-based financial professional, and longevity-solutions financial professional.

FIGURE 1

A New Frontier

Figure 1 presents the evolving value of financial professionals as a continuum that is defined by two axes. The y-axis indicates the Depth of Relationship that the financial professional has with the client and the client’s extended social network or family. The x-axis shows the Breadth of Discussion, indicating the range of topics and issues about which the financial professional engages the client in discussing while planning and financing for longevity. The greater the depth of the relationship with the client (and their family/social network), and the more comprehensive the connection of finance with actual longevity solutions, the more valued the relationship.

Transaction-Based Value: The transaction financial professional provides relatively traditional services that focus on investment and financial security. Primary client engagement is made typically with one member of the household, (e.g., the husband). Discussions are centered on the ‘number’ needed to ensure a secure retirement. Interactions certainly include planning, but are typically guided by algorithms of what an average family may need in retirement, (e.g., housing and healthcare costs). The value of the financial professional-client relationship rests on investment growth. Interactions between the financial professional and client are limited and are primarily about transactions undertaken to achieve a quantified goal.

The transaction financial professional’s value proposition of product knowledge and investment growth is core to financial-advisory service. However, such a client/financial professional relationship is tenuous because it rests on the success of investment-product outcomes alone. Given the limited interaction and context of the relationship, financial professional knowledge of the client’s family, decision dynamics, and health are severely constrained. Moreover, the same technology applications that enable seamless transactions, investment visibility, and cost calculators also make the transaction-based financial professional the most likely to be automated or replaced by solutions that empower the client to become a do-it-yourself investor.

Drawing upon a healthcare example, consider the devolving role of the general practitioner who only provides care for the most basic conditions, such as the flu or allergies. Routine services traditionally obtained from general practitioners are now being provided by nurse practitioners equipped with computer-based algorithms in local drug or grocery stores. But medical specialists or physicians who have deeper relationships with their patients have proven more difficult to replace.

Planning-Based Value: The planning financial professional expands his or her relationship with the individual client beyond investment strategy. A concerted effort is made to include the partner or spouse as a planning unit. While quantified investment objectives remain a priority, the planning financial professional initiates a broader discussion about planning objectives, such as where a couple may wish to live in retirement.

The planning financial professional is also more likely to provide additional financial services, including life insurance, college-education financing, new home loans, and more. Seminars are frequently used to further engage the client, but the topics are most often limited to focused financial issues, such as understanding Social Security or investment opportunities presented by new emerging technologies.

The planning financial professional seeks additional engagement with clients via online platforms that provide supplementary information or thought-leadership—(e.g., developing a more refined retirement plan, asset allocation, or tax and estate planning)—a level of detail that can’t be communicated within the limited time constraints of face-to-face meetings.

While meeting all of the critical and core value propositions expected of financial professional, the planning financial professional does not fully address what clients will need in longer life: A clear idea of what decisions they may find themselves facing in old age, how much those choices and challenges may cost, and how to identify the necessary trusted services to complete the jobs that will arise.

Longevity-Solutions: The longevity-solutions financial professional enjoys the greatest degree of client intimacy and has the deepest relationship with his or her clients and their families. The longevity-solutions proposition also offers the widest range of discussions and product solutions. For example, client seminars engage entire families on topics that address the broader context of living longer (e.g., education and professional development across the lifespan) or the future treatment and cost of managing chronic disease. Adult children may be engaged as an integral part of the relationship and, where appropriate, serve to facilitate discussions of what the client and his or her family may want in old age, such as where to live and how.

The longevity-solutions financial professional focuses on and facilitates more in-depth discussions about health and wellbeing. Such discussions are critical to providing insights to the client, but also facilitate conversations that may reveal issues, such as a diabetes diagnosis, which will have profound implications on the costs of healthcare in advanced age.

Longevity-solution discussions go beyond investment and planning alone to focus on the income that will be necessary to address specific needs in later life. Moreover, the longevity-solutions financial professional serves as a connector between clients and trusted, vetted services that provide solutions to the jobs of longevity.

For instance, the financial professional may maintain relationships with downsizing services, regional providers of senior housing, or aging-in-place certified home contractors that can advise homeowners on how best to update a home while modifying it to support older age. Product innovators may find that ‘purposeful products’ that connect specific investment income with a branded service provider for jobs such as home maintenance may be especially appealing.

Since longevity-solutions financial professionals address a wide range of lifelong issues, they are better able to engage clients across their life stages. Rather than focusing only on the future, the longevity-solutions financial professional becomes relevant immediately, and that usefulness only increases over time. Such a financial professional may connect adult children in their 40s to geriatric care managers and eldercare services to care for aging parents, or provide career-transition services for 50-something clients who want to continue to work but also want a change.

In short, the longevity-solutions financial professional’s value is that he or she helps provide financial security along with a map of what older age may present, who can be enlisted to help, and how to pay for it all.

An Evolving Business Model of Longevity & Advice

Longevity and the changing social context of aging are increasing client needs and expectations. Investment, money management, and planning expertise will remain critical to the core value proposition of financial professionals. But those competencies may only comprise a small part of what clients may seek from financial professionals.

Broadening the conversation and deepening the relationship with clients and client families may require a different advisory business model. No one will expect financial professionals to be part social worker, social psychologist, home contractor, or eldercare advisor. However, a new generation of clients may value solutions, not just advice. Financial professionals now stand at a frontier: the new business of longevity. That business will provide them with opportunities to engage with their clients over a lifetime, on more topics, more often, and with greater intimacy. Ultimately, providing such highly valued service will be compensated.

Execution on this emerging business model will require a greater emphasis on creating teams of expertise. Today’s financial professional has the potential in the next few years to transform his or her framework of retirement into a foundation for longevity planning: the center of an ecosystem where clients can save, invest, plan, and connect with solutions that will translate living longer into the reality of living longer, better.

Next Steps

| 1 | Download The Future of Advice workbook |

| 2 | Evaluate your current business model on pages 4-5 |

| 3 | Within one week, choose a category from pages 7-9 and complete the action steps |

1 Vital Statistics Rapid Release, Number 015, cdc.gov, 7/21

2 Civilian labor force participation rate by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, 1999, 2009, 2019, and projected 2029, bls.gov, 9/20

3 How Much Do You Need for Retirement if You Live to Be 100?, newretirement.com, 6/20

4 Living into the 22nd century, brookings.edu, 1/20

5 2020 Census Will Help Policymakers Prepare for the Incoming Wave of Aging Boomers, census.gov, 12/19

6 Millennial life: How young adulthood today compares with prior generations, pewresearch.org, 2/19

7 Baby Boomers’ Expectations of Health and Medicine, journalofethics.ama-assn.org, retrieved 10/19

8 Social Media Fact Sheet, pewresearch.org, 4/21

9 What age are women having babies? What the falling fertility rate tells us, usatoday.com, 5/24

10 About Chronic Diseases, cdc.gov, 4/21

11 2020 Report: Caregiving in the U.S., aarp.org, 5/20

12 Despite Pandemic, Percentage of Older Adults Who Want to Age in Place Stays Steady, aarp.org, 11/21

13 Historic numbers of older Americans are now living by themselves, Washington Post, 9/24

The MIT AgeLab is not an affiliate or subsidiary of Hartford Funds.