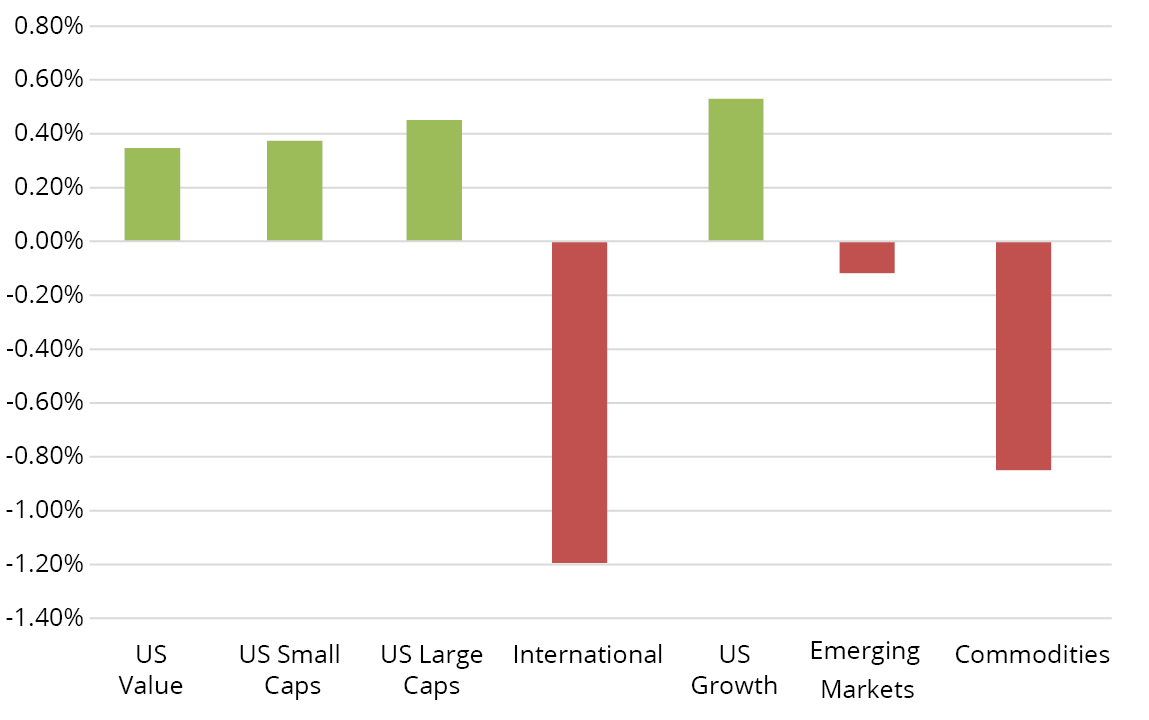

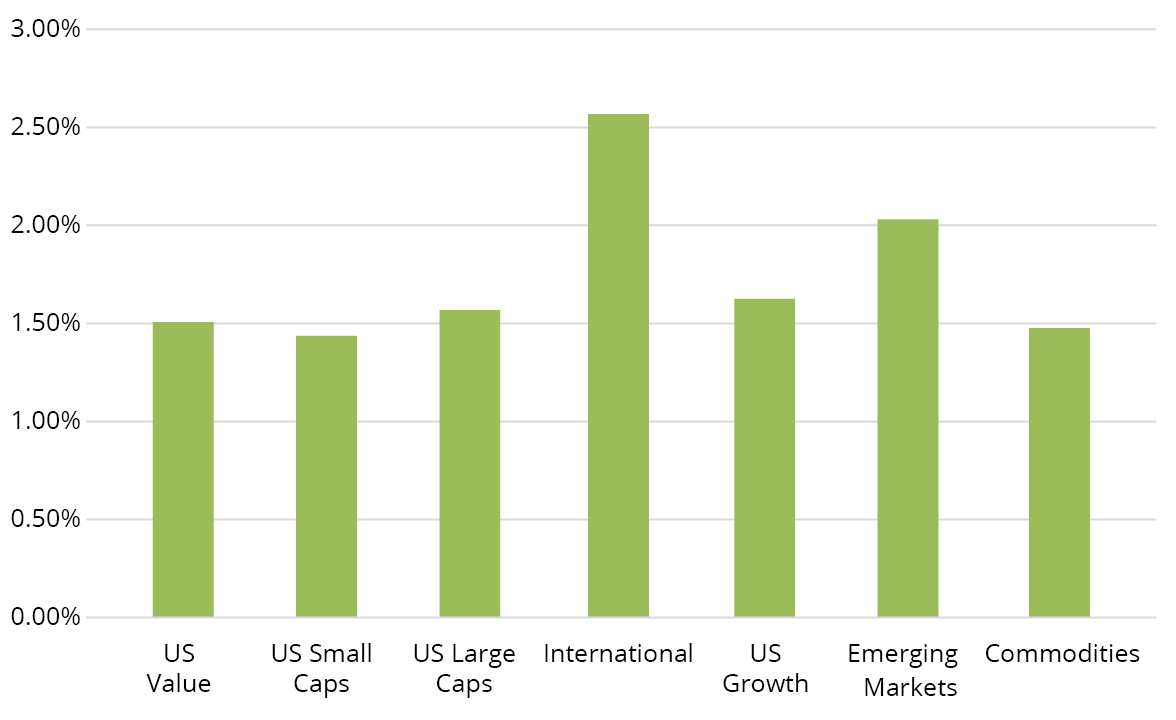

Commodities are represented by the Bloomberg Commodity Index, dating back to 1/1/91, which is a broadly diversified benchmark that measures the performance of futures contracts on physical commodities across major sectors, including energy, agriculture, and metals.

Emerging Markets are represented by the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, which tracks large- and mid-cap equities across emerging economies worldwide, covering approximately 85% of their free-float-adjusted market capitalization. Because the net return version only dates back to 1/1/01, performance reflects a combination of the gross return index (from 1/1/88) and the net return index (from 2001) to provide a more complete historical perspective.

International is represented by the MSCI EAFE Index, which represents large- and mid-cap equities across developed markets in Europe, Australasia, and the Far East, excluding the US and Canada, providing international developed market exposure.

US Growth is represented by the Russell 1000 Growth Index, which measures large-cap US stocks with growth-oriented characteristics, such as higher valuations and stronger forecasted earnings growth.

US Large Caps are represented by the S&P 500 Index, which is a market capitalization-weighted price index that tracks 500 leading large-cap US companies across major industries, widely regarded as a primary benchmark for US equity market performance.

US Small Caps are represented by the Russell 2000 Index, which represents the performance of 2,000 small-cap US companies within the broader Russell 3000 Index, serving as a key gauge of small-cap equity trends.

US Value is represented by the Russell 1000 Value Index, which captures large-cap US stocks exhibiting value traits, including lower valuations and slower growth expectations.

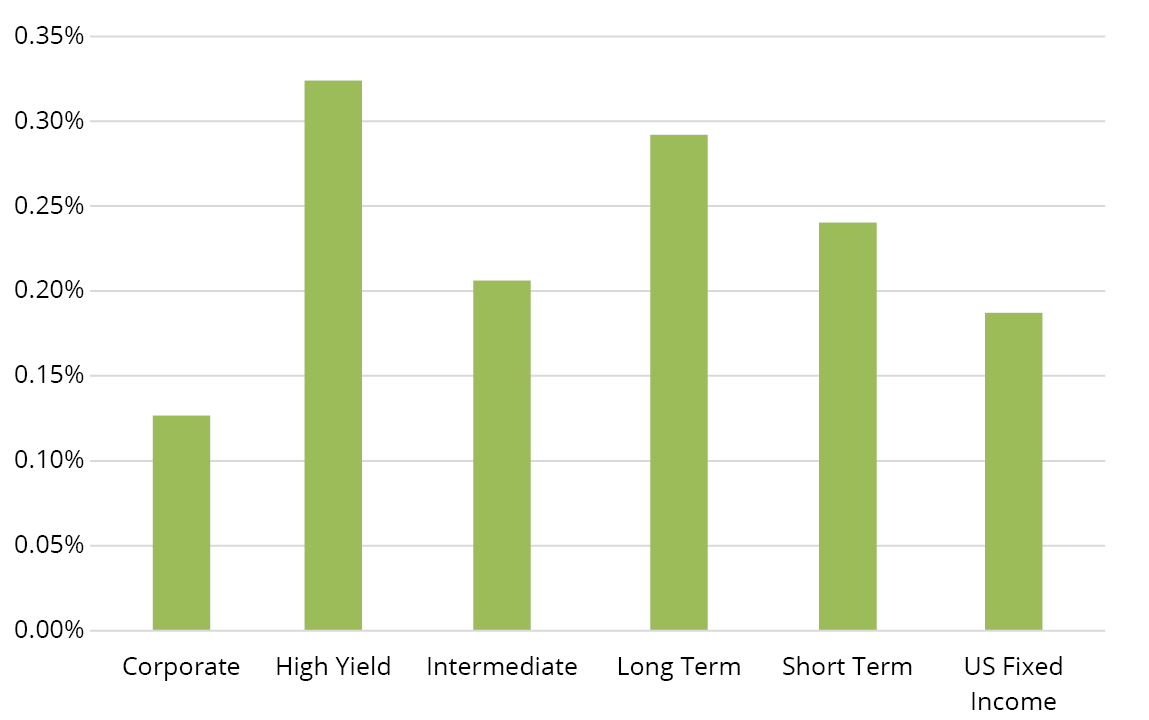

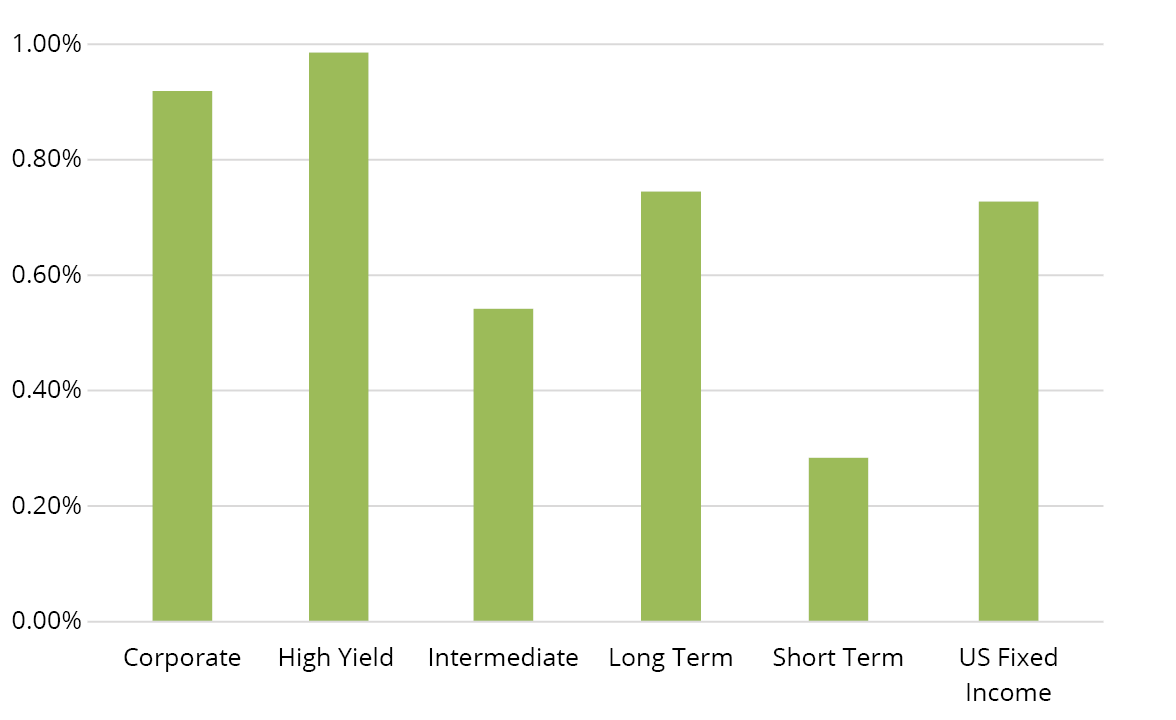

Corporates are represented by Bloomberg US Corporate Bond Index, which is a market-weighted index of investment-grade corporate fixed-rate debt issues with maturities of one year or more.

High yield is represented by Bloomberg US High Yield Corporate Bond Index, which is an unmanaged broad-based market-value weighted index that tracks the total return performance of non-investment grade, fixed-rate publicly placed, dollar-denominated and nonconvertible debt registered with the SEC.

Intermediate is represented by Bloomberg Intermediate US Treasury Index, dating back to 2/1/87, which tracks US Treasury securities with maturities between 1 and 10 years, providing a measure of intermediate-term government debt performance.

Long Term is represented by Bloomberg Long-Term US Treasury Index, dating back to 2/1/87, which measures the performance of US Treasury bonds with maturities of 10 years or longer, reflecting long-duration government debt exposure.

Short Term is represented by Bloomberg Short Treasury Index, dating back to 2/1/88, which represents short-term U.S. Treasury securities with maturities under one year, offering insight into near-term government debt returns.

US Fixed Income is represented by Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index, which is composed of securities that cover the US investment-grade fixed-rate bond market, with index components for government and corporate securities, mortgage pass-through securities, and asset-backed securities.

Important Risks: Investing involves risk, including the possible loss of principal. • Foreign investments may be more volatile and less liquid than U.S. investments and are subject to the risk of currency fluctuations and adverse political, economic and regulatory developments. These risks may be greater, and include additional risks, for investments in emerging markets or if focused in a particular geographic region or country. • Small- and mid-cap securities can have greater risks and volatility than large-cap securities. • Fixed income security risks include credit, liquidity, call, duration, and interest-rate risk. As interest rates rise, bond prices generally fall. • Investments in high-yield (“junk”) bonds involve greater risk of price volatility, illiquidity, and default than higher-rated debt securities. • Investments in the commodities market may increase liquidity risk, volatility and risk of loss if adverse developments occur. • Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss in a declining market.

This information should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation to buy/sell any security. In addition, it does not take into account the specific investment objectives, tax and financial condition of any specific person. This information has been prepared from sources believed reliable, but the accuracy and completeness of the information cannot be guaranteed. This material and/or its contents are current at the time of writing and are subject to change without notice.