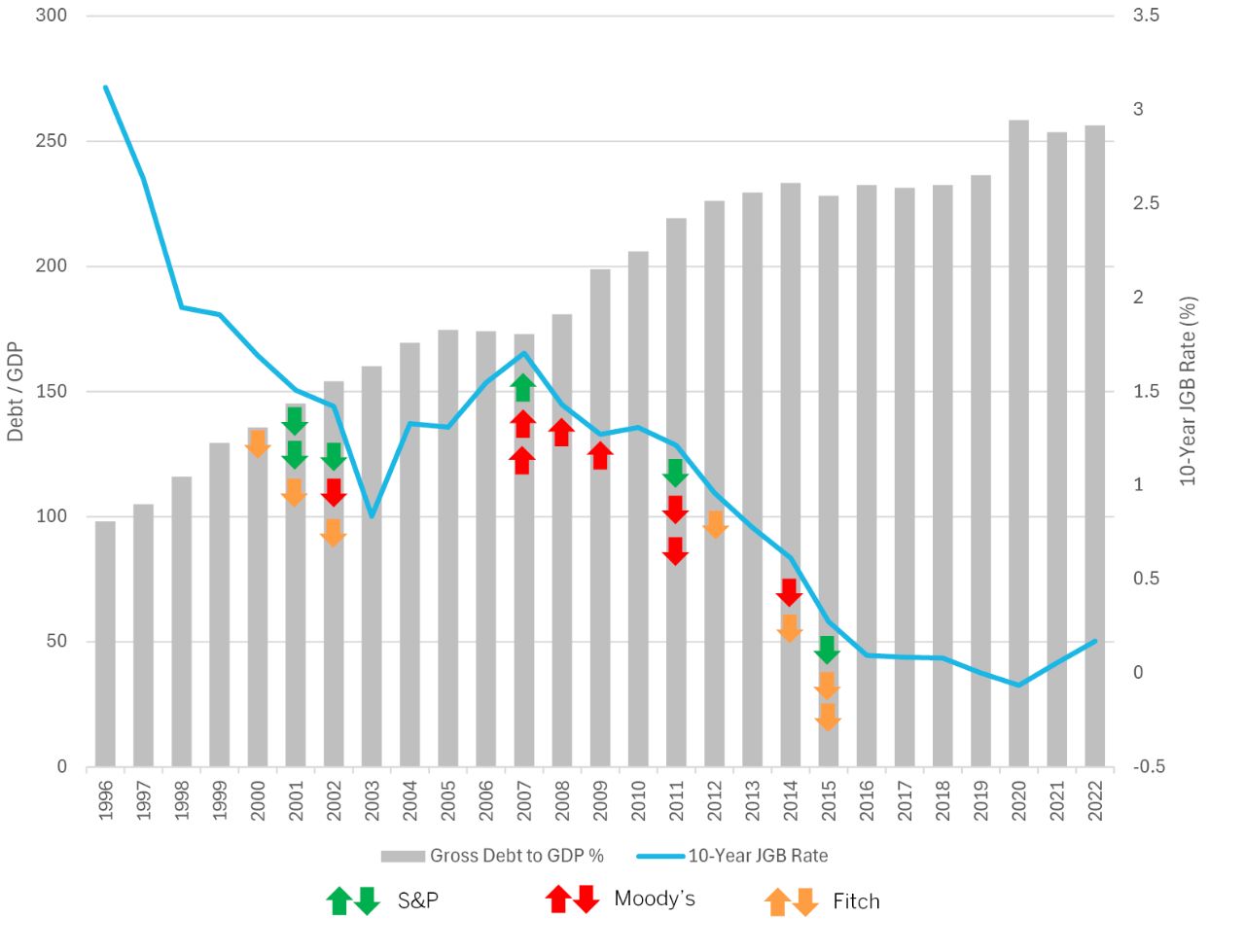

“The downgrade from the top rating of Aaa to Aa1 reflects the increase over more than a decade in government debt and interest payment ratios to levels that are significantly higher than similarly rated sovereigns. Successive US administrations and Congress have failed to agree on measures to reverse the trend of large annual fiscal deficits and growing interest costs.” - Moody’s Investor Service, May 2025

I was a young Treasury official in the Office of Debt Management during the summer of 2011, when Standard & Poor’s downgraded the US for the first time amid a debt ceiling standoff. At the time, I hoped it was a misjudgment—that the US would retain its other pristine AAA ratings, a reflection of the world’s most dynamic and wealthy economy.

But over the 14 years since that initial downgrade, the other agencies have followed suit. Fitch downgraded in August 2023, and now Moody’s followed in May 2025.

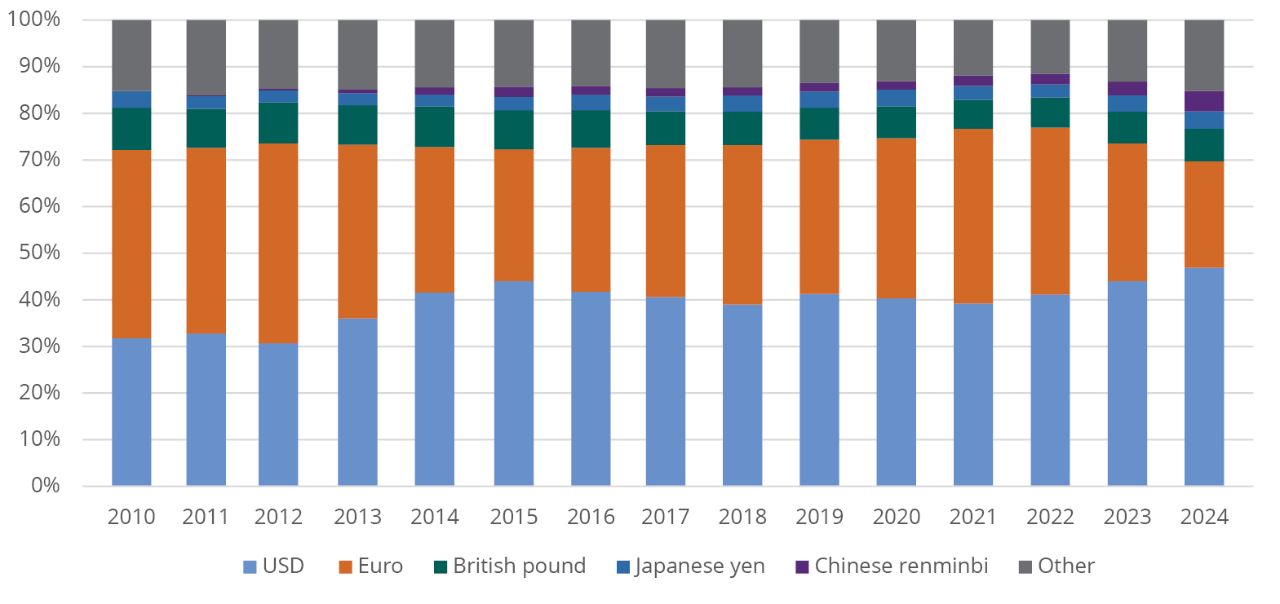

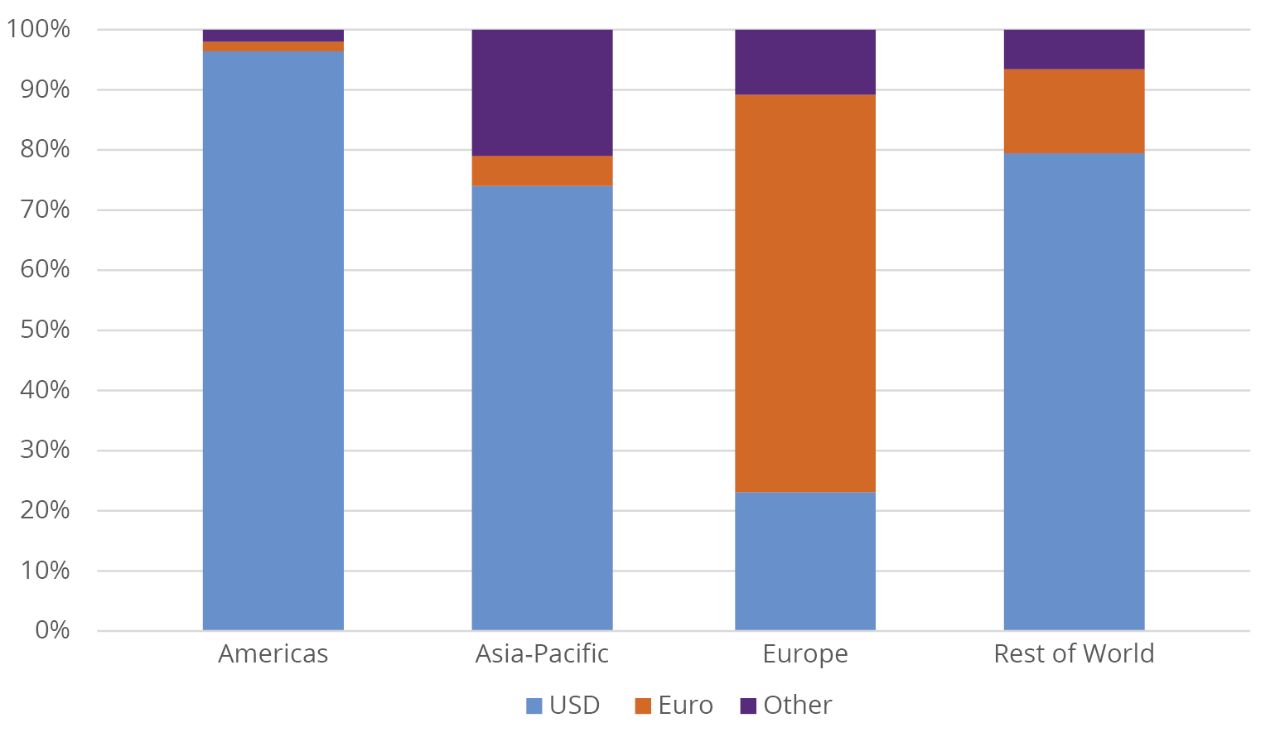

Despite the sting, it’s important to step back and assess the implications for global capital markets. The rating is intertwined with broader issues: reserve currency status, debt sustainability, domestic policymaking, and the viability of foreign alternatives to the US dollar (USD).

The downgrade has, in many respects, had a limited impact on market functioning. However, there are areas where it could begin to influence conditions in US capital markets. The rating itself is best understood as an output, or rather, a reflection of the country’s financial and institutional health. If it begins to serve as an input into how market participants assess risk and allocate capital, the potential for adverse consequences may grow over time.